On March 21st, 2021, FARC dissidents and FANB (Bolivarian National Armed Force) troops engaged in combat in the Páez municipality, State of Apure. Particularly, in La Victoria, a town bordering the Colombian department of Arauca, clashes between the militants and the army of Venezuela extended through April 3rd. The incident left 8 FANB members deceased, 9 FARC guerrillas, and 32 suspected FARC members captured (1).

Since the rise of Hugo Chávez to power in 1999, Venezuela was known to provide a haven to Colombian leftist guerrillas, which was true until recently. In the context of the internal conflict in Colombia, Venezuela provided key corridors to the Colombian guerrilla for drug smuggling, refreshment, and resupply. Even after the signing of the Peace Accord in Colombia, the Venezuelan government continued to provide support and deep territorial access (2, 3, 4, 5).

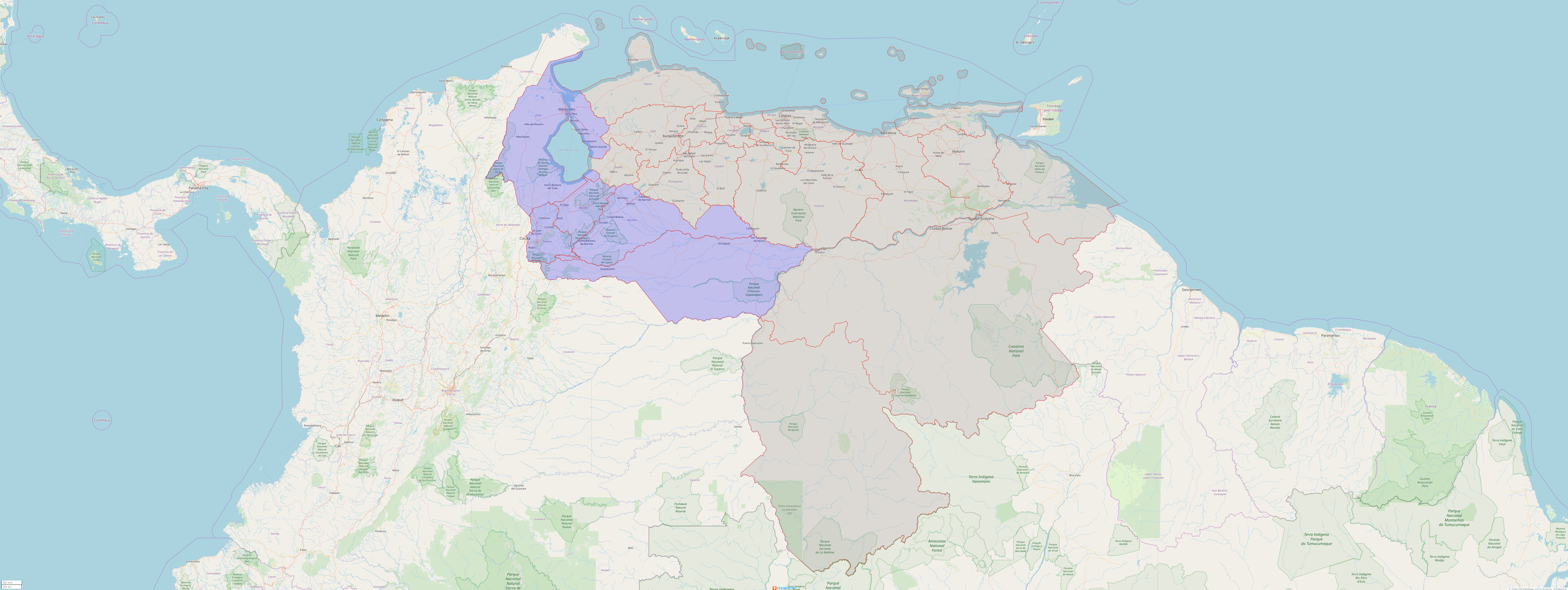

Despite FANB troops were able to tackle the guerrilla in Apure, within the highly prioritized area known as the Andean Front (or Half Moon) – a group of Western states bordering Colombia comprised by Zulia, Táchira, Mérida, Barinas, and Apure (blue in the map below) – Colombian insurgent groups have since long ago established their presence in Táchira, Zulia, Amazonas, Bolívar, and Falcón (6).

The reason behind the shift in policy towards the Colombian guerrillas is a matter of survival. Caracas is just not willing to further absorb the risk of open interstate conflict with Colombia for continuing to provide support to the guerrillas, especially when such a course of action would more likely end up with the collapse of the regime.

To extend its survival, the Maduro regime has adopted fundamental policy changes in recent months. Changes no one would have thought remotely possible, given the hardcore and radical policies implemented since the very beginning of the Chavista era. Changes such as the de facto dollarization of the economy (7), the willingness to open foreign oil investments (8), and the unprecedented discretional powers given by the “antiblockade” law to Maduro (9), are agonal respirations of a regime fighting to catch its last breath.

The Risk of Interstate Violence

On April 7th, 2021, Diosdado Cabello, vice-president of the PSUV (United Socialist Party of Venezuela) and one of the most influential figures of the Chavista regime, made a threat against Colombia affirming that President Duque’s government facilitates its territory for the United States to attack Venezuela and “if we go to war with Colombia, we’ll take it to their territory” (10), during his TV show “Con El Mazo Dando.” Despite Cabello’s acrobatic interpretation of the recent combats between FANB and FARC, this does not seem to be driven by Bogotá, despite a renewed determination to end the support previously given by Caracas to the guerrillas.

On April 13th, Maduro announced the deployment of 1,000 Chavista militias in the State of Apure, after declaring FANB had regained control of the area (11). Whether the measure was a propagandistic one or has the intention of preparing logistic support for combat units, the fact is that the tension in the area continues to be high, since both Venezuela and Colombia have increased their military deployments in the Apure-Cauca region, and continue to exchange accusations in the international arena.

The main risk posed by further destabilization in Venezuela is the probability of conflict spreading across the deep, porous, and inhospitable bordering territories of Amazonas and Bolívar, into Brazil; and the Western Venezuelan Half-Moon, into Colombia. This, combined with the economics of illegal narcotics production and smuggling, creates a potential for a self-sustainable conflict loop.

A Civil War Ahead?

The peculiar situation of Venezuela can easily be sparked into a civil war, given three main facts: the illegal economy of drug production and smuggling; the level of indoctrination and combativeness of Chavista groups; and the availability of weapons among civilians.

As the history of the Colombian conflict shows, drug production and smuggling can be an integral part of the economics and sustainability of terrorist groups (12). In the absence of the conflict between the US and the Soviet Union, guerrilla organizations such as FARC and ELN found a way to sustain and even expand their influence without the necessity of having a plan to conquer political power. Either by producing narcotics themselves or by taxing other producers and smugglers, they were able to maintain their operations for several years. With that in mind, one can easily assume that in case of an imminent existential threat Maduro may easily engage in illegal activities to mobilize his assets since Caracas has already been accused of engaging in the large-scale international drug trade (13) through the Cártel de Los Soles criminal organization. In such a scenario of open conflict, and especially if Maduro is removed from power as a consequence, the formation of Chavista insurgent groups is highly probable.

As for the level of indoctrination, one can infer that given the institutionalization of the Chavista ideology since the early 2000s and at all levels of public administration, there are already hundreds of militias prepared and willing to go to war for the revolution (14). Lastly, there are about 1.5 million firearms in the hands of civilians (15), which represent around 84.63% of all small weapons in the country (16).

The already vast arsenals across the country, mixed with the access to narcotics as a revenue source, and the ideologization of institutions, beyond and out of the political control make the civil conflict scenario a catastrophic one that can potentially spread across Northern South America.

By Luis Campos Pérez – Political Risk & Threat Intelligence Analyst, Americas.