On October 12, Facebook’s secret blacklist of “Dangerous Individuals and Organizations” (DIOs) was revealed by the American web magazine “The intercept”. The list includes more than 4.000 people and groups which are considered dangerous and therefore can be banned by the social network, such as terrorists, armed groups, militarized social movements and violent non-state actors. The leaked blacklist sheds light on the measures used by the social network to counter online radicalisation, terrorism propaganda, hate speech and violence.

Analysis

Facebook’s attempts to moderate the content shared on its platform is not a recent phenomenon. Since 2012, the social network has been moderating or banning some of its users in an attempt to respond to accusations that the platform was used to promote violence, terrorist propaganda and recruitment. Jihadist and terrorist groups have been using social networks like Facebook, Twitter and Telegram either to spread their extremist ideology or to recruit people since the early 2010s.

As a consequence, one of Facebook’s early measures was the introduction of a ban on “organizations with a record of violent or terrorist activity” to its community standards. However, the fight against terrorist propaganda demanded global coordination and partnerships. Thus, in 2017 Facebook, along with Microsoft, YouTube and Twitter, formed the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT). Moreover, Facebook has deployed a new strategy based on Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools which, combined with human expertise, can help to detect terrorist and extremist content. In particular, Facebook uses AI for image and video recognition and language detection to flag dangerous posts to be removed.

However, over the past years, Facebook has been intensifying its restrictive policy which now seems to have evolved into a proper blacklist. To help moderators deal with the restrictions, a three-tiered system has been elaborated, which classifies DIOs and regulates under what circumstances they can either be banned or restrained:

- Tier 1: includes entities who cause “serious offline harm,” such as criminal organizations, terrorist groups or groups who are likely to spread hate and violence.

- Tier 2: includes “violent non-state actors”; mostly armed groups that threaten states’ security. In particular, it includes many armed factions in the Syrian Civil war.

- Tier 3: includes non-violent entities which violated Facebook’s policies in terms of hate speech or DIOs.

Forecast

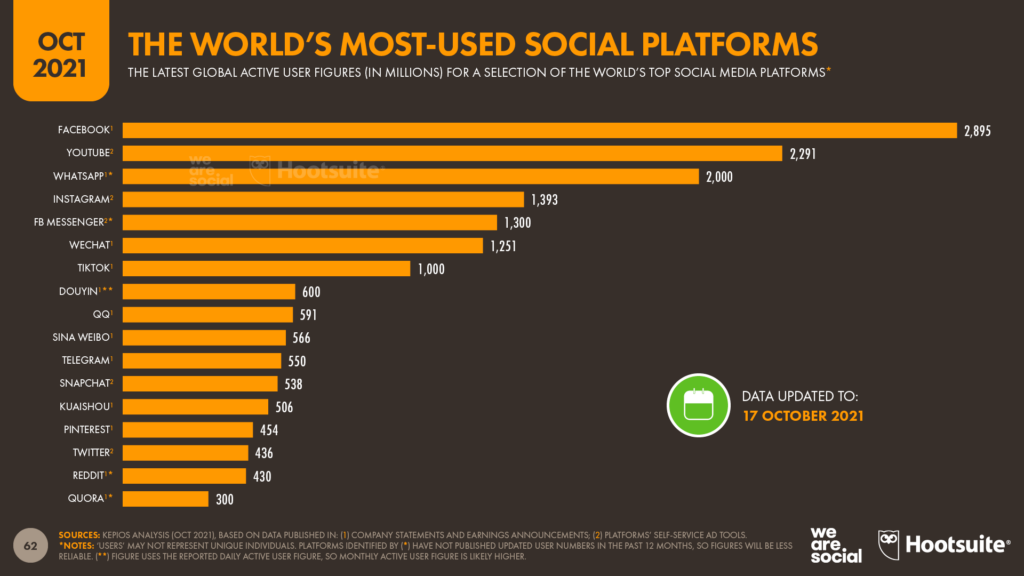

Facebook is the most used social network in the world with over 2.89 billion of monthly active users, followed by Youtube (2.29 billion) and Whatsapp (2 billion). Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that many people and organizations found in Zuckerberg’s platform the perfect forum to share radical ideas.

However, now that both the blacklist and the moderation guidelines have been made public, two possible scenarios may emerge. On the one hand, radical groups and individuals may learn how to circumvent the ban and the moderation guidelines, thus continue operating undisturbed. On the other hand, the moderated entities might consider moving their narrative to other, less restrictive, platforms like Telegram, Parler or Gettr, as it has already happened in the past.

For instance, in 2015 Facebook blocked Islamic State’s content on its platform, and therefore many IS militants migrated to Telegram, which also provides end-to-end encryption for conversations. Similarly, during the U.S. elections in November 2020, many conservatives and right-wing supporters of former U.S. President Donald Trump moved to Parler, which gained 3.5 million new users in just one week. More recently, in January 2021 Facebook and Twitter banned the accounts of former U.S. President Trump, following the violent riots at Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. In that instance, Telegram gained 90 million new users. The newly born micro-blogging platform Gettr, which describes itself as “founded on the principles of free speech, independent thought, and rejecting political censorship and cancel culture”, also attracted many IS and right-wing users.

In conclusion, the fight against online radicalisation and extremism is far from being won. Even though the problem can be partially contained in one platform, it easily emerges elsewhere due to the lack of a common policy among the providers of micro-blogging platforms. Regulating micro-blogging platforms could bring about positive changes when it comes to the spreading of violent messages online. However, this would require finding common ground on the definition of “free speech”; a topic that is more likely to polarize societies than unite them.

By Chiara Cassarà, Artificial Intelligence & Political Risk Analyst at Hozint – Horizon Intelligence.